I recently examined the challenges of B2B developer marketing. One area I touched on was the importance of really understanding stakeholders’ sometimes divergent “hot buttons.” That went hand-in-hand with another lesson: You’re not addressing just one target, but a whole lineup of influencers and decision-makers who have a say in the sale.

That’s because when doing any kind of B2B technology marketing, you’ve got to embrace the hard truth that one size *never *fits all when it comes to needs, value propositions and messaging.

One person’s idea of product value may be another person’s “meh,” to put it bluntly, even if they’re working within the same four walls, even on the same project. You just can’t assume your targets will all interpret your message the same way. That’s especially true when you’re trying to capitalize on marketplace trends. (That is to say, throwing out some buzzwords that sorta fit your product and hoping they stick.)

You think these buzzwords just sell themselves?

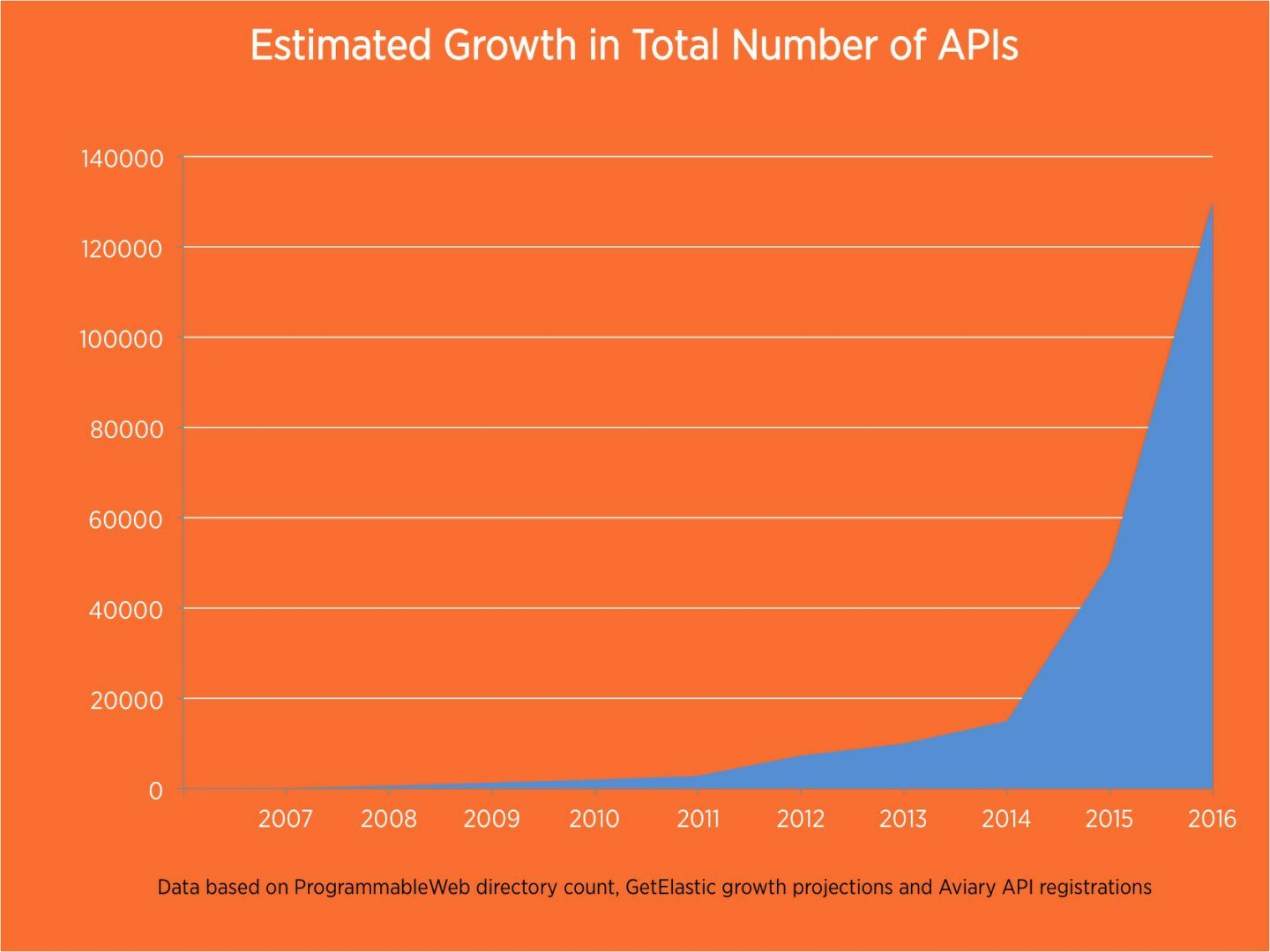

Let’s illustrate this with an example ripped from today’s tech headlines. What’s a B2B technology trend that’s on fire, where some providers might think their product practically sells itself? One that’s presumed to be on the Christmas list of every CIO, CTO and Director of Engineering? How about “microservices?”

I see you’re smiling in agreement. (Or are you smirking? It’s hard to tell from here.) “Microservices” isn’t just a bit of marketecture fluff. It’s a bit of codified shorthand that distills many of the architectural trends of the past several years. My own company’s offerings, like many of our customers’ (and maybe yours, too), are designed around a microservices architecture.

So, microservices are a real thing that real technologists do real work with. But that doesn’t mean that namedropping the term is necessarily an effective way to appeal to a B2B tech buyer. (Aha—you were smirking earlier!)

But what about focusing on the implicit functional and architectural qualities instead?

- Does your so-called microservice meet all the right mandates: small, each focused on “doing one thing and doing it well,” modular, elastic, resilient, minimal and complete unto itself?

- Is it a clean and complementary addition to their own enterprise architecture?

- Does it solve a specialized, difficult problem and deliver demonstrable ROI and payback?

That’s a little closer—you’re focusing on qualities and benefits rather than relying on jargon. But even then, going to market with the attitude of, “We’ve built a better mousetrap—isn’t that obvious?” isn’t going to move a lot of business beyond the first few customers who share your vision.

Even in the cloud, tech marketing is a lot like any other B2B relationship

If it sounds like you may be challenged to establish your bona fides on the most basic level, you’re right. Your target buyer isn’t about to make a snap decision. In fact, most aren’t in a position to make a unilateral choice much of the time.

In that way, B2B tech buyers fit the “typical” template of a B2B buyer:

- They don’t make impulse buys, but well-parsed purchases where an entire buying team might be involved, especially at a large enterprise running a sizable architecture. The buying process will have multiple stages, too, including torture-testing your pride and joy to see if it breaks.

- They’re smart and informed, and they’ve seen a zillion or two products in their time, some even pitching the same promises you are. They do copious research and have their ear to the ground at GitHub and other places where they’ll get the real skinny on you and your track record, have no doubt.

- They’re playing for big stakes, because failure can not only lose them their job but can result in their company taking a bullet, too. So they’re virulently protective of the infrastructure they’ve assembled.

- They’re harder to reach, especially the farther up the ladder you go, because real decision-makers studiously avoid taking cold calls or giving advertising the time of day. You reach them with relevance using tools like content marketing, advocacy strategies, participation in industry forums and events, and other more credible touch points.

- They respect relationships and the work you put into developing a sound and steady one with them by getting to understand their challenges and ambitions. It’s a long-haul effort, and it’s entirely about earning trust, often the hard way.

Just because they may share attributes across the board with other B2B prospects, though, you still have to customize your message and approach to suit the individual persona of each role-player who’s part of the buying process.

Another thing to remember: They’ve got the power, more than ever. Vendors, once upon a time, had more control, but the cloud blew up that paradigm. Part of what they expect from the entire buying experience you deliver is ease and convenience, too, just like consumer companies deliver. That’s why vendors with good brand recognition and easy-to-use trials beat out the competition.

All of this circles right back to where we began: Who, exactly, are you trying to convince and convert?

Who is your buyer? I mean, really?

As with terms like “microservices,” marketing and sales personas are a convenient shorthand for describing complex characteristics. But like buzzards, it’s all too easy to jump to the shortcut: “We have an enterprise buyer” or “We market to tech executives.” In reality, those personas are usually quite a bit more nuanced.

You’re obviously aiming to connect with key influencers and decision-makers. Thus, you’re obliged to do a huge amount of research, networking, social media and industry outreach to figure out who it is you need to target within each organization and what their hot buttons/pain points might be.

Remember, though, that the final decision-maker may not be the person doing the assessment and testing, and he or she may only have a momentary presence during the entire buying experience. They may kick off the process and show up at the end, but somebody else is doing the grunt work in between. Even so, you’ve still got to educate and sell them when they eventually show up.

You might be tempted to make the CTO or CIO a primary target, and that might make sense if you were selling an entire enterprise-scale microservices architecture solution to a company that’s migrating away from a monolithic approach or considering it. They’re concerned with big-picture work: How to update enterprise infrastructure without breaking the bank, planning deployment, network and system management, integration testing, risk management practices and so on.

If you’re only selling a widget, especially if it’s a comparatively small widget in the grand scheme of things, the CTO/CIO may not be the person buttering your bread, frankly. But it’s good to make sure that person has heard your name somewhere, in a good way: Attending top-tier conferences, showing up in the trades they read or doing traditional “awareness marketing” via advertising and PR can help with that.

The Software Architect is charged with articulating the vision behind whatever architecture is being deployed. He or she builds models, devises spec documentation for components and apps (like yours!) and validates and re-validates that architecture.

Depending on the company’s structure, the software architect may be a primary target, and certainly, he or she is a purchase influencer/ratifier worth keeping in the loop. But very often, they’re not going to be directly involved with initially assessing your product.

The Director of Engineering comes close to being your sweet spot, though. She or he is on the spot for ensuring proper execution to hit the company’s goals for its technology stack and has a hand in determining the tools that make it happen.

They’ve got the job because they love building things, so showing off the elegance and suitability of your app by talking engineer-to-engineer is the way to go.

The Developers underneath the Director of Engineering may be excellent targets if they’re in the right position to be recommenders or specifiers with enough juice to get your product formally bench-tested. They’re probably avid participants in the developer communities where word-of-mouth and code sharing rule, and proselytizing them can be an open door to real opportunity.

What good can you do them in return? Beyond solving a particular need and helping them build their own knowledge base, you’re giving them the opportunity to look good to their bosses—no small motivation.

Depending on your particular offering, DevOps and Security teams also are in the mix. They might be responsible for assessing your operational requirements and reliability and conducting security audits. And they’ll certainly be responsible for ongoing monitoring of your service when it’s in production.

Even in the age of the cloud, gatekeepers like Procurement or Sourcing Managers still play a role. They’re likely to at least be a formal part of the process for larger deals. They issue RFPs or bid requests, manage the evaluation process and attend to all the nitty-gritty of finalizing a contract or license.

They may (or may not) have a direct role in bringing you to the attention of others in the organization, but you should bend over backward to help them build a business case for your product, especially one that appeals to the multiple stakeholders they’ve got to satisfy.

The closer you get, the better you look

So, are these folks personas? Sure—but more than that, they’re people. And no amount of white-boarding value props can replace the power of genuine empathy and connection. That takes work, and there’s no shortcut.

Certainly, you’re working toward developing a replicable model to scale your efforts. It’s why constructs like personas and leveragable trends such as microservices are critical to B2B marketers.

But your long-term success is going to be built on actual relationships with people: prospects and customers. Forging those ties now and maintaining them throughout the years to come will bring you far more eventual reward than selling a customer a one-off app. Even if it’s a really great app.

This article originally was published at Marketing Land/MarTech Today.